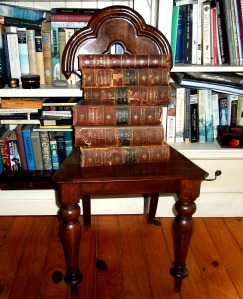

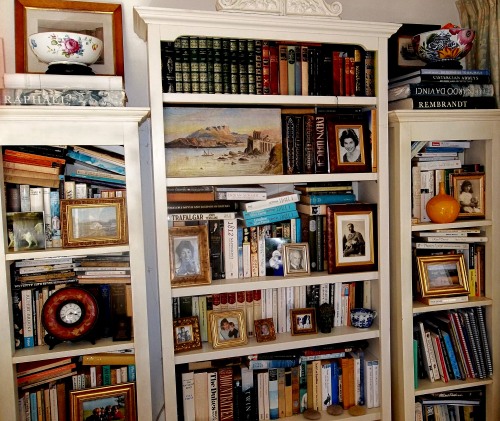

I sometimes torture myself by imagining I’m on a desert island and can only take ten books with me. I look around at the walls of book-shelves in the sitting room and bedroom and spare room, and wonder how to whittle them down to the ten most treasured books I wouldn’t want to be without.

As in the BBC radio programme, no Shakespeare or the Bible allowed, though I’d be sad to let the Bible go – not for religious reasons – but for the sheer poetry of the prose and the beauty of so much of the writing, for some of the stories embedded in the teachings… like the story of Ruth for example, or the Song of Solomon… and the Beatitudes, and ringing phrases like: ‘I am as sounding brass or a tinkling cymbal if I have not charity’ .. or the exquisite words of Psalms like 139, which ends with: ‘…’if I take the wings of the morning and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea, even there shall thy hand find me, and thy right hand shall hold me’.

But having surrendered the Bible what would I take? Bernadine Evaristo, this year’s Booker prize-winner, says she hates Jane Austen and Virginia Wolfe… but while l’d agree about Virginia, as an afficionado who used to read Jane Austen’s six novels once a year, I’d have to disagree with her findings on Jane. (Real Austen fans are called Janeites. I once wrote a piece for an anthology of raves about Jane Austen, and attending the book launch party was somewhat bemused to find myself among some fans wearing long Regency dresses, and sporting shawls and fans)

Which of the six would I take? No contest. In my younger days, I’d have plumped for ‘Pride and Prejudice’… or ‘Persuasion.’ But now I’d go for ‘Mansfield Park’ which I used to think was the dullest of her books. Now it’s my favourite. I love the picture of Georgian country life, the amateur theatricals with all the tensions and emotional turmoil, and the irritating, contradictory and sparkling array of people, especially the two villains, who’re the most attractive characters in the book. But most of all, I love that picture of elegant English country life in my favourite period of history before the Industrial Revolution, when squalor and hardship and smoking factory chimneys had not altered forever a peaceful pastoral society. (Even if they didn’t have good dentists).

To balance that picture of aristocratic country life I’d take Thomas Hardy’s ‘Far from the Madding Crowd’, my favourite of all his books, crammed with authentic country lore and farming custom, just slightly later in time that Austen’s novel.

And to round off this wallowing in homesickness for another time and place while on that desert island, I’d take George Eliot’s tome, ‘Middlemarch’, a great book described by the despised Virginia as ‘the magnificent book which with all its imperfections is one of the few English novels for grown-up people.’

It’s a huge canvas describing with acute psychological insight many typical characters of both town and country in early Victorian England. For me, it’s a picture not just about English town life of that period, but a profound study of character, both shallow and profound, of good and evil in the shape of materialism, and of the compromises demanded by society. So, nostalgia and homesickness sorted – there’s several more choices to go.

Top of the list would be Barbara Tuchman’s splendid history, ‘The Guns of August’, an account of the first ten days of WW1, but fleshed out with vivid and witty accounts of how Europe got to that point, and an analysis of the main protagonists… fascinating history, accurate psychology, and telling insights, all delivered with wit and humour, so that often I find myself chuckling as we traverse the terrible terrain of one of the great turning points in the history of Europe.

I would have to take ‘The Snow Leopard’ with me, by Peter Matthiesson. It’s the story of his journey into the remotest regions of the Himalayas on his search for the then almost never seen and legendary snow leopard. It’s a many layered tale with deep spiritual undertones, and read like all these other books, many, many times.

Getting a bit panicky now, with only three more choices to go. I think I’ll reach for Truman Capote’s story of love and war, ‘The Grass Harp’. It’s told with deceptive simplicity, the characters utterly loveable, and gloriously eccentric as despair drives them to desperate measures. They are the odd ones out, who finally step outside the norms of society to assert their individuality, and when they say what they feel, they slice through the hypocrisies and cruelty of narrow-minded small-town officialdom.

I love diaries and have a huge collection of them, ranging across time, from seventeenth century Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn in Charles 11 reign, to Georgian Parson Woodford and Parson Gilbert White, Victorian Francis Kilvert, through to the two world wars, to the randy diaries of Alan Clark, the notorious womaniser and politician, and the delicious, hilariously funny fictional diaries of Adrian Mole, my favourite being ‘Adrian Mole and the Weapons of Mass- Destruction.

I toyed with the last of the Bloomsberry’s, Frances Partridge’s ‘A Pacifist’s War’, her diary filled with details of an idyllic life in the beautiful country house where the painter Carrington lived with writer Lytton Strachey before his death and her suicide. Her war years are peopled with a stream of intriguing/incestuous Bloomsberry illuminati who came and feasted with Ralph Partridge and Frances while dwelling on their moral high-ground as conscientious objectors.

I decided on something more uplifting. Inspiring integrity was what I was looking for. Should I take Alanbrooke’s war-time diaries, or Cadogan’s account of appeasement and diplomacy before and during the war, or Klemperer’s diary chronicling the terror of the Nazis, and his worry about the fate of his beloved cat? It finally had to be put down when Jews were no longer allowed to keep pets. Klemperer, a distinguished university professor, ended up in the bombing of Dresden which allowed his wife and he to disappear in the chaos, the only positive thing I’ve heard about that raid.

No… I finally settled on the two volumes of John Colville’s diaries. He was Churchill’s private secretary during the war, and the parade of kings, queens, statesmen and generals, society ladies and foreign diplomates makes absorbing reading, quite apart from the affectionate and admiring portrait of the great man himself.

Throughout the cliff-edge years of war, Churchill is revealed as an irascible but brilliant, kind, intelligent and chivalrous aristocrat in the best sense of those words, without a trace of snobbery or small mindedness. Perhaps too original and spontaneous to be described in conventional terms as a gentleman, he emerges as a magnificent human being who poured his huge stores of energy, humanity and vision into his country and the struggle against one of the greatest tyrannies in history.

The last and tenth book is a tantalising choice, trying to choose between two of my favourite diaries. ‘Mrs Milburn’s Diary’ is written by a woman with no literary talent, but an abiding love for her only son, who was captured before Dunkirk and endured POW camp for the rest of the war. Her letters sent via the Red Cross, and his to her were usually months old by the time they reached their destination, so she began writing a diary chronicling life in his home and family and community.

It’s a prosaic day to day telling about the price of woollen vests going up, the annoying man at Matins every week who coughs all the way through and ruins the service, the evacuees who stay briefly, the long cold nights sitting in their primitive underground air raid shelter in the garden – doubly important to them- as they lived in the country outside Coventry, and lost many friends in the catastrophic bombing raid which destroyed that city. It’s an insight into a way of life now gone… when, even during the war, she picked primroses every spring in the woods, packing them up in damp cotton wool and sending them to friends in the city.

She records the routines of church going, weekly shopping, Mother’s Union meetings, working for the WVS (Women’s Voluntary Service) dealing with the erratic gardener, the feckless land girls, a chaste glass of sherry shared with old friends. The annual rhythms of the seasons’ rituals celebrate a slice of civilisation which had its own small satisfactions, sorrows and minor victories.

Or, do I go for ‘Burning,’ a diary of a year living in the Blue Mountains in Australia? Kate Llewellyn is a poet, and her book is crammed with exquisite metaphors and similes, quirky people, precious moments of beauty, meditations on history, recipes, travels and gardening. I read it often, not just for the drama of human tragedy and pain which also takes place during that year, but for the sheer beauty of the writing.

As CS Lewis observed, ‘we do not enjoy a story fully at the first reading. Not till the curiosity, the sheer narrative lust, has been given its sop and laid asleep, are we at leisure to savour the real beauties’. He also suggested that someone who only reads a book once is ‘unliterary’, whatever that means! But I certainly agree with him on both counts when he says “You can never get a cup of tea large enough or a book long enough to suit me.”

So I can’t decide between these two life stories – regularly ‘savoured’, and will beg my invisible and sadistic inner voice to let me have them both… to have whittled down my choices to eleven from hundreds of books is no mean feat, which meant leaving out precious favourites like Leigh-Fermor’s ‘A Time of Gifts’, his vivid description of European civilisation before the Nazis destroyed it

As I mulled over this imaginary exercise, and visualised myself roaming a tropical paradise, alone like Robinson Crusoe, I realised that by choosing a handful of books to be my companions in this solitary life, I wasn’t using any carbon footprint, and many of the books were recycled – bought from second-hand bookshops around the world via the internet, or acquired from op-shops and the like.

Many of them of them too, like Capote’s ‘The Grass Harp’, I’ve owned since the sixties, and are worn from regular loving re-readings when I savoured every aspect of the writing and the human condition. In a book on educating children read in the seventies, I found a wonderful thought, that literature is the logbook of human experience, and that’s how it seems to me too.

For this solitary island existence, Christopher Morley, an American writer, gave me words that seem particularly apt: ‘when you get a new book, you get a new life –love and friendship and humour and ships at sea at night -… all heaven and earth in a book.’

The written word survives e-books, the internet, texting and all the other apparent advantages of technology. It has been with us from the earliest times, when the Sumerian civilisation evolved writing around 3,000 BC, and the first literature was created by a Sumerian author a thousand years later. Books and words may be the one blessing and means of communication that survive in the aeons to come.

Books will always be the ‘log-book of human experience’, and can hand on the riches of our civilisation to generations still unborn. And for the present, they can be a comfort, a companion and a treasure. They inform and educate, amuse, console, entertain and inspire. They are indispensable and irreplaceable. They make life on a desert island bearable!

Food for Threadbare gourmets

We’re living dairy free at the moment for various reasons, and I discovered to my delight that it’s perfectly possible to make a decent white sauce using olive oil instead of butter.

So using the juices from a roasted chicken from the night before, I made a rechauffe… fried some chopped bacon and mushrooms, made the sauce, and stirred a bouillon cube and the chopped cooked chicken, bacon and mushrooms into it. Flavoured the mix with salt, pepper and nutmeg, and served it on rice.

To cheer up the plain boiled rice, I fried a grated courgette in olive oil and garlic, plenty of salt and pepper and stirred it into the rice. We ate it all with green beans and didn’t miss the cream or milk at all!