Auckland, with volcanic island Rangitoto across the harbour

A Life – Another instalment of my autobiography until I revert to my normal blogs

I searched the world for an egalitarian English- speaking country. Canada was too cold. Australia meant living in another large crowded city in order to find a job. So I explored New Zealand – reading its history written by well- known historian Keith Sinclair. On learning from it that women had had the vote since 1893, that back then employers were required to provide a seat for shop girls to sit on if they needed to, and that the two- day weekend for everyone to spend with their families was the norm, I decided this was the place.

It sounded a kind and old- fashioned society. Which it was, and that didn’t seem a dis-advantage. I began reading NZ newspapers at the FCC (Foreign Correspondents Club) trying to get a feel for this new country. I found that the city nearest the equator which would be big enough to have a newspaper that would employ women was Auckland.

I had no money for our air fares so went to see the Dean of S John’s Cathedral to see if their fund for distressed gentlewomen could help. He directed me to the British Legion, who generously covered all our fares and expenses. It galled me that they did so because my father and ex-husband had been in the army rather than because I had been, but I swallowed my pride, and thanked them for their largesse.

Just before we left, my ex-husband back in England, placed an injunction on me to prevent me leaving with the children. This involved another expensive legal action and employing an enormously expensive counsel this time.

At a conference before the case, the pompous and rather arrogant counsel began by telling me not to speak unless spoken to, and to answer his questions with a yes or no. Towards the end, he had picked up so many false trails that I broke his rules and butted in and put the facts chronologically as he needed them. He sounded irritated and asked why I hadn’t said all this in the first place and couldn’t see that he’d created the situation by treating me like a half-wit.

The case was heard in chambers, with the same judge from my divorce, who once again decided the course of my life without even looking in my direction as I sat at the other end of the table. Unusually he gave me custody, care and control, a rare decision which the British High Commission in Wellington declined to believe a few years later when I applied for a separate passport for the children so they could visit their father back in England. The logic of applying for a passport to send them to their father if I’d kidnapped them in the first place defied me. But harassment was such a normal state of affairs for women in those days that many, like me, took it for granted, and just worked around it.

I could only afford to pay for the minimum sized box, four cubic feet, in which to pack our belongings. I ordered it five foot by four by three, to accommodate a favourite picture, painted by Chinese school children. It was called ‘House Under the Moon’, and later, a friend who was curator of various well- known art galleries said that if an adult had painted it, it would have been a masterpiece.

Besides this treasured picture which I couldn’t bear to leave behind, I packed a pair of Bokhara rugs, a black lacquer Chinese box containing our china, some silver, an antique mirror, a few other pictures, two Chinese lamps, some carefully culled books, and a pair of bamboo Chinese collapsible bookcases that looked like Hepplewhite designs. I was so ruthless that I’ve since regretted many small things that would easily have fitted in – treasured pieces of china, an art nouveau pewter goblet, good linen. But then, the burning of boats suited my mood.

So I packed up my life, and spent the last day with Pat Hangen. Our plane was delayed by eight hours while another plane was fished out of the harbour at the end of the runway at Kaitak. Landing or leaving this fabled island was always dangerous – flying between tenement blocks and drying laundry to land or take -off.

I had never really come to terms with life here. In Victoria, the heart of the rich bustling city, a newspaper seller had a pitch outside Lane Crawford, the Harrods of Hong King. The windows just behind him were tastefully arranged with fabulous diamond encrusted jewellery; and I discovered that he and his wife and children lived and slept on the pavement under his newspaper stall.

Yes, I tried to assuage my western conscience by delivering clothes and blankets. But the shocking gaps between haves and have-nots, especially in the cold winters, bothered me as much as cruelty to children and animals still do… Now, as we flew out on the second of August 1970, I peered down at the lights of Hong Kong and the places we’d grown to know so well in the last four years.

Deepwater Bay, Repulse Bay, Stanley Bay. These were the places in which we had lived. In each one, I was always conscious, over twenty years after the events, of the battles fought in these places by the defenders against the terrifying Japanese army. Deepwater Bay was where the Japanese landed to cut off the defenders from each other on Hong Kong island. I knew the very spot at Repulse Bay, where two British soldiers swam for it, and got to Stanley Point, only to be killed in the massacres there.

I used to look up at the woods behind the Repulse Bay Hotel and wonder where the drain was where the women and children had tried to seek safety from the bullets. And I never drove to Stanley Point and past the site of St Stephen’s College without remembering the slaughter of the patients and doctors there, the rape and murder of the nurses.

Wongneichong Gap no longer exists. The cliff face and rock formation have long since been demolished to make way for a wider road. But whenever I drove through it then, either forking right to Deepwater Bay or straight ahead for Repulse Bay I paid homage to the Canadians who made their last stand against the Japanese there, and fought with such incredible bravery to the last man. It felt sometimes as though they were still there, I was so conscious of their ghostly presence.

The memories of the signing of the surrender on Christmas Day had been briskly banished from the unchanging Peninsula Hotel in Kowloon across the harbour. Yet the few trees left in Victoria, on Hong Kong island, still bore the marks of the dreadful barrage of artillery from the Japanese across the water. They were riddled still with shrapnel, but somehow were bravely surviving a worse battle now against traffic and fumes.

We landed in our new country among green fields dotted with white sheep. Driving into Auckland in the middle of the antipodean winter, gardens were blooming with daffodils and camellias, jasmine and purple lasiandra bushes. It seemed like paradise.

The journey had been an unexpected ordeal. My friendly doctor had given us all our injections but had forgotten to sign the documents. When we landed in Brisbane in the freezing dawn at six o clock, the elderly and obstructive airport doctor discovered this – but refusing to even look at our weeping smallpox vaccinations as proof, sent us back to the plane under armed guard, to the astonishment not only of me, but the other passengers.

At Sydney I thought I’d avoid the hassle and stay on the plane for the stopover. Alas, it was not to be… after a long delay on landing, a posse of armed police boarded the plane, and announced over the loudspeaker that I was to report to them with my children. Struggling through the now irritable standing passengers with their luggage, waiting to leave the plane, we were marched off and put in a freezing room.

August in Hong Kong is hot, hot and this was frosty mid-winter in Sydney. In spite of our warm clothes we were all shivering with cold – and in my case with fear. Finally, after nearly half an hour I opened the door in a rage, and found an armed guard standing in front of me. How long am I going to be kept here I asked. It’s not my business to say he replied. I have never felt so utterly powerless.

Then a doctor arrived, young and reasonable, looked at our arms and sores, laughed and said it was all a storm in a tea-cup, and we were allowed to board the plane, this time unescorted. Halfway across the Tasman, checking our documents for arrival in Auckland, I realised that the Sydney doctor hadn’t signed the medical documents either.

It never crossed my law-abiding mind to sign them myself, so positioning myself at the back of the queue this time, I went through another hostile interrogation on landing in Auckland, and ended up bursting into tears when one of the truculent officials demanded “Well, where’s your husband?” “I haven’t got one,” I wept and they let me through.

More trials awaited me at customs, where our three suitcases contained not just clothes but sheets and towels and cutlery! Coming from Hong Kong, customs were sure I must have muddy shoes or other dangerous items covered in bacteria which would pollute this pristine place. Finally, a friend of a Hong Kong friend who had said he’d meet my plane, was actually waiting for us, even though I’d only met him once.

The tired children were as good as gold and sat in the back seat of his car amid the eight fringed legs, two fiercely wagging tails and the panting jaws of his two golden retrievers. John was a bachelor, and it never crossed his mind that we were exhausted, so he drove us all over his city in the fading twilight, to show us beauty spots and architectural delights, before taking us to his flat on the fringes of the city. His father had just died, so instead of leaving us at a hotel as I’d expected, he lent us his flat while he stayed with his bereaved stepmother.

Frightened though I was by the experience of landing in a new country, with no money, no home, no job, and no friends, it felt as though the tide was turning. I seemed to have found a generous and kind friend already.

The next day, having lit the fire, switched on the lamps, got the children settled at the dining table, enjoying a properly cooked supper, and a low happy babble of conversation filling the comfortable room, John arrived. I could see he just loved the idea of being welcomed home, offered a drink, and entertained by two lively children. He stayed for hours, with me once again on the brink of exhaustion. Meanwhile his dogs had begun what became a regular routine for some years. They trotted through to the bedroom where the children were tucked up, and checked they were alright before rejoining us. Life began to seem rather sweet.

The next day, his neighbour, who was a journalist, gave me the names of the people to apply to for a job at the two main Auckland newspapers. I still have the envelope on which she scrawled the names and phone numbers. One of the names eventually became my second husband. After meeting the children, she also asked to use them for a television programme about taking children to the zoo, as their clear articulate voices meant they were ideal for her purposes – local children mumbled, she said!

John’s best friend also arrived with John and being in the car business helped me buy a second- hand car on hire purchase, a necessity in a huge city with minimal public transport. Thus equipped, I turned up for my two job interviews. The worst part of this was knowing no-one with whom to leave the two five and six- year- old children. So I parked on the top floor of a quiet car park.

Torn between the fear of them being kidnapped if I left the car door unlocked, or trapped inside the car if I locked it and there was a fire, I straddled both nightmares. I left them with a picnic- cream buns and chocolate biscuits- and left the car unlocked, telling them if there was a fire, to go to the edge of the car park, lean over and yell fire. I then made my way un-easily to my job interviews.

To be continued

Food for threadbare gourmets

Friends arrived unexpectedly for drinks, one of them allergic to gluten in a big way. My usual standby – rice crackers – seemed stale, so I had to improvise. I sliced a potato very thinly, fried the slices in olive oil, and used them as a base for smoked salmon and cream cheese, while the rest of us consumed gluten packed blinis. I made a good helping of garlicky aoli, to eat with sticks of celery, courgettes and carrots -that did for us all – and along with a plate of olives, gherkins, and cubes of cheddar cheese and a lovely bottle of Reisling, we managed !

Food for thought

Outside the open window

The morning air is all awash with angels.

Richard Wilber

South Vietnamese troops battling the Viet Cong in Saigon during TET offensive

South Vietnamese troops battling the Viet Cong in Saigon during TET offensive

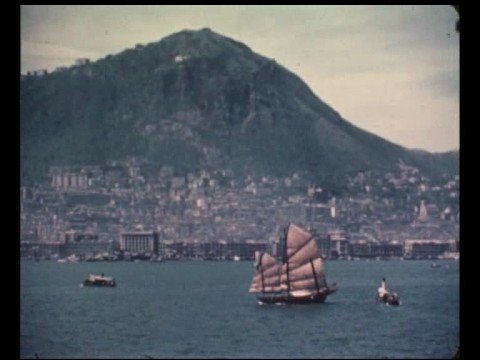

Hong Kong in the mid-sixties

Hong Kong in the mid-sixties